Most of my work is in general philosophy of science, i.e. the philosophy concerned with general methodological and epistemological questions about science. I’ve done work on theory-ladenness, prediction and explanation, ad hocness, scientific discovery, scientific realism, meta-philosophy, and most recently, experimental philosophy. Many these topics I tackle systematically in my book Theoretical Virtues in Science. See below for more details.

Theory-ladenness

It has been argued by some that scientific observations are theory-laden, i.e., colored in one way or another by the theories we hold (see my encyclopedia article “Observation and Theory-ladenness” for various forms). But often data in science do not have the nature of an observation: data are often numerical values produced by instruments. I have therefore thought about the ways in which experiments and experimental outcomes may be theory-laden (see my paper “Theory-laden experimentation”). Contrary to an influential account, I also think that “data-to-phenomena” inferences can be (and in some fundamental discoveries demonstrably are) theory-laden.

Much of my early work has been concerned with this topic.

Prediction and explanation

Prediction and explanation are central concerns of science. I have worked on both of these topics (separately).

Predictivism is the thesis that a theory’s predictive success is better evidence for that theory than (already known) evidence that the theory accommodates. Although this thesis has a lot of intuitive pull, there is plenty of historical evidence that it’s incorrect – at least for some domains of science. The rationale for predictivism that have been offered are either not very generalizable or beset with problems. See “Novelty, Coherence, and Mendeleev’s periodic table” and chapter 3 of my book.

I’ve long been interested in explanation, and in particular, in the popular interventionist / counterfactual account by Woodward. I recently argued that there are explanations that explain why counterfactual dependencies have the form that they do have. See my paper “Micro-model explanation and counterfactual constraint”. I have also written critical assessments of Craver’s mechanistic account of explanation (“Mechanistic explanations: asymmetry lost?”) and Bokulich’s account of model explanations (“Explanatory fictions: for real?”)

Ad hoc-ness and theoretical fertility

Philosophers of science were once very concerned with ad hoc hypotheses: Popper’s and Lakatos’ influential account were built around the idea that ad hoc hypotheses are to be avoided. But what makes a hypothesis ad hoc? Why is it supposed to be a bad thing? I have discussed the classical accounts of ad hocness (and a couple of more recent ones) and proposed my own account in my book in chapter 5.

There is a view (mostly associated with E. McMullin’s work) according to which it’s a major strength of a theory to overcome anomalies (i.e. counter-instances) without having to resort to ad hoc hypotheses. I discussed this account in chapter 6 of my book and in my paper “Theoretical Fertility McMullin-style”.

Experimental PhilSci

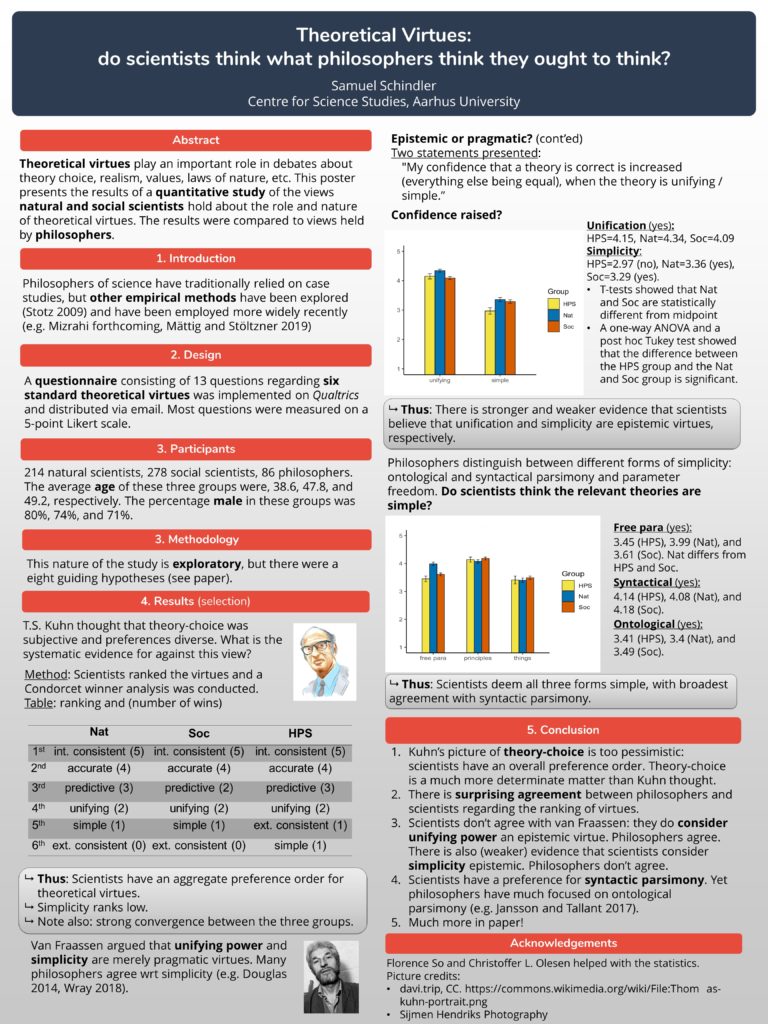

In recent years I have started to do empirical experiments with scientists on various issues in the philosophy of science. My first paper that has come out of this work is entitled (self-explanatorily) “Theoretical Virtues: do scientists think what philosophers think they ought to think?”. You can view a conference poster and a talk on the paper here:

I have done more experimental work on predictivism and intuitions, which I hope to write up soon.

Meta-Philosophy and XPhi

Meta-philosophy concerns itself with the methods used by philosophers. I’m interested in meta-philosophical issues both in the philosophy of science and other areas of philosophy.

I have thought about how it is possible for philosophers to make philosophical generalisations from historical case studies (I argue because case studies function like philosophical “model organisms”) and how it is possible to articulate rational norms about science on the basis of historical facts (I show how it is in what I call the “Kuhnian mode of HPS”).

I’ve spent a fair deal of time (as part of a project) thinking about the use of intuitive judgments in thought experiments. In particular, I’ve been thinking about parallels between what’s known as the “method of cases” in philosophy, and (i) judgments made in thought experiments in physics (see “Armchair Physics and the Method of Cases” and “Are thought experiments ‘disturbing’?”) and (ii) acceptability judgments in linguistics.

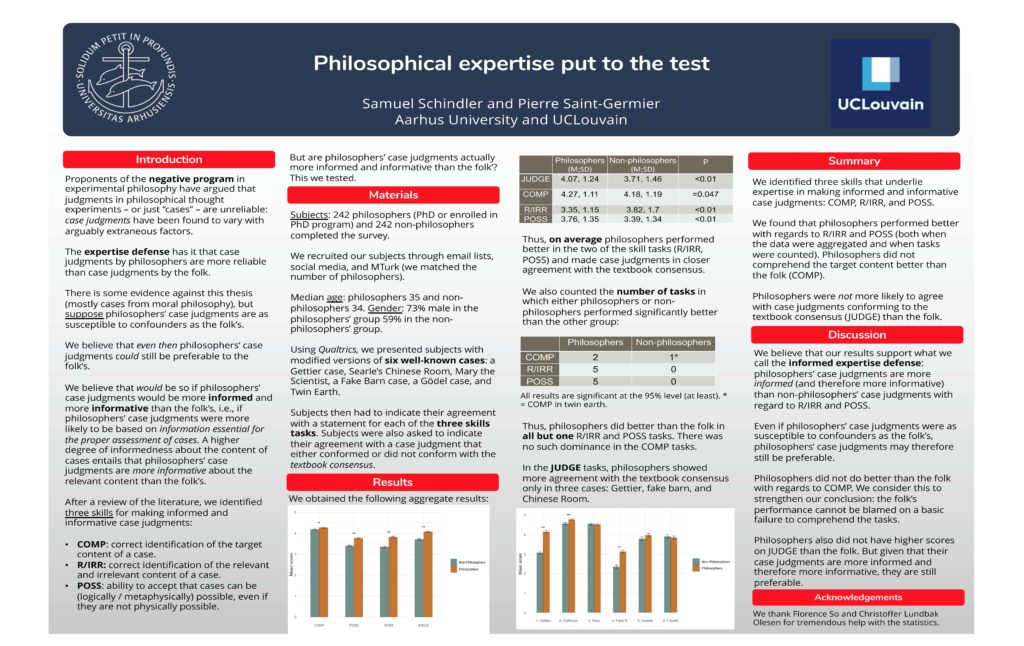

I also thought about whether experimental methods of obtaining acceptability judgments in linguistics are superior to informal methods (I argue No, see my book chapter “Experiments in Syntax and Philosophy”). Finally I’ve also done experimental research on the much disputed question of whether there is any philosophical expertise in the method of cases (we argue Yes, see our paper “Philosophical Expertise put to the test” and the poster below).

Realism debate

Scientific realists and antirealists argue about how confident we can be about what science’s best theories tell us about the world. The realism debate hasn’t been a major focus in my work, but in my book on theoretical virtues I have argued that the realism debate can be re-shaped in interesting ways if we first re-assess theoretical virtues on the basis of the history of science.

In the book I have tackled what many consider to be one of the most severe challenge to the very debate: the charge that the debate is meaningless because the base rate of true theories eludes us. In the book I also make a couple of other realist arguments.

Scientific discovery

When philosophers talk about discovery, they usually have the “two contexts distinction” in mind: the context of discovery and the context of justification. The former essentially refers to questions relating to how scientists come to design their theories. There is very little work on scientific discovery as usually understood, namely as discovery of stuff in the world. One seminal contribution is an often overlooked paper by T.S. Kuhn in the journal Science, in which Kuhn makes an important distinction between two different kinds of discovery (the paper forms the basis of one of Kuhn’s Structure, but the distinction is much less clearly made there).

I wrote a paper in which I defend Kuhn’s distinction against some criticism and propose ways of improving the distinction (see my paper “Scientific discovery: that-what’s-and what-that’s”).